In my more peevish moods, I give vent to my spleen. Years ago, I found that I could no longer listen to NPR for a simple reason: too many of the hosts sounded too inarticulate to be taken seriously as representatives of an organization belonging broadly to the intellectual logosphere of our country. As much as I enjoy podcasts, I’ve found that even many of the smartest writers whose work I admire seem to have yielded entirely to the tyranny of the word ‘like.’ Now I struggle to find pleasure in any of the ones which aren’t framed as comedy because I find myself frustrated at the progressive degradation of conversational sentence structure.

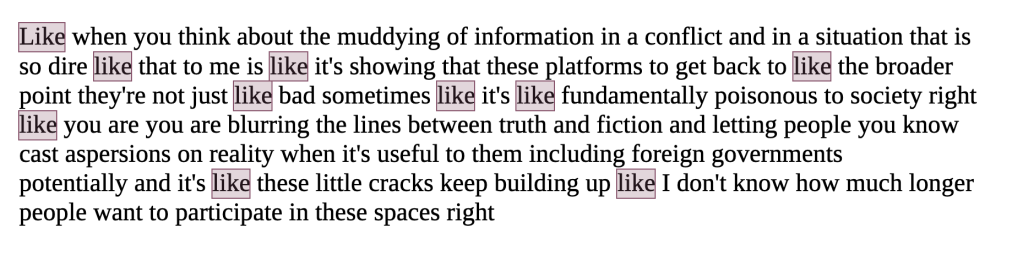

In Taylor Lorenz’s latest interview with Charlie Warzel, it struck me that it is par for the course now for professional journalists to conduct interviews employing syntactic structures that might well have been but a parody of an inarticulate high schooler in the 90’s or early aughties. Both Lorenz and Warzel expressed their thoughts with a combination of gestural/affective utterance, memetic suggestion, and a mass of likes strewn about (319 total). As a mode of communication, this puts heavy demands on the listener because you have to supply most of the reasoning underlying their assessment of the Twitter influencer location reveal scandal. (I should note that I like Lorenz’s tech reporting and feel entirely sympathetic with her views, which is precisely why I listen regularly, but also why I find myself annoyed by this.) A section of the transcript:

Somehow, I cannot take “they’re not just like bad sometimes like it’s like fundamentally poisonous to society” seriously. I recognize that the epistemic turbulence which the internet has wrought is indeed fundamentally poisonous to society, but it’s hard not to think that the poison has spread so far that even the internet’s sharpest critics don’t realize what a horrific effect the inundation of brain rot and the ceaseless insipid chatter online have had on their capacity for verbal articulation.

I realize that this complaint will make me appear like a crank to many readers, who feel far less uncomfortable with this aural assault than I do. I know that linguists like to burnish their progressive credentials by explaining this away as a filler or a hedge and then proceeding to suggest that being annoyed by its use is a sign of a socially reactionary or prejudiced disposition. But I don’t find the phenomenon so galling when people are having casual conversations. It seems however that serious ideas that require serious airing ought to be clearly, if not forcefully, expressed. A discussion on an important topic, conducted by two journalists who follow that topic, and produced for intentional dissemination to a regular audience requires a different register than chitchat does.

Not to stretch the point, but perhaps the reason why many public intellectuals are undervalued today is that they don’t, even to the lay ear, express themselves like intellectuals. The internet is less democratizing than demoticizing. Now that most of what are obnoxiously called ‘thought leaders’ are as halting and inarticulate as the average citizen, they have ceded one of the distinguishing tokens by which they might be recognized as thoughtful people.

According to an old literary anecdote that often circulates unsourced and variably quoted, Karl Kraus suggested, in reaction to the Japanese devastation of Manchuria, that such atrocities would not be happening if only people had cared more for the proper placement of the comma. While the point of the story is to draw him as a caricaturized pedantic stickler, it also hints at a greater application: the health of civilization is tied to its modes of expression. As ours becomes more telegraphic, reliant upon memetic reference, and generally more driven by the conveyance of affect than by a chain of linear reasoning, so too do people become less able to discern what is being done to their brains.

Leave a comment